More dementia training is needed to stop residents attacking care home staff

Over a third of care homes have had a staff member attacked by a resident, yet this could be prevented if care homes gave their staff proper dementia training.

Care homes are beginning to realise that looking after people with dementia requires well trained staff.

Dementia is not just a case of memory loss. More than half of all people with dementia experience behavioural symptoms such as depression, delusions, loss of inhibitions or aggression.

The damage in the brain that causes dementia may also cause behavioural changes, by damaging the part of the brain that regulates behaviour. Aggression may also be a reaction to a person with dementia being unable to understand the world around them or misinterpreting the actions of others.

Aggressive behaviour often occurs in situations where care staff must assist with very intimate needs like feeding, bathing or toileting, as a person with dementia may be fearful or view this as an invasion of their privacy.

However good dementia training can show care workers how to act in these sort of situations so they don’t scare the person or make them feel they are invading their privacy.

When people hear about aggression and violence in care homes, they tend to think of the residents being victimised and abused by care workers, rather than the other way round.

Care staff can be on the receiving end of a lot of physical and verbal abuse, particularly when they are caring for people with dementia or those with mental health problems.

A survey carried out by found over 70 per cent of care homes had records of a person with dementia being verbally or physically aggressive during a three month period and 22 per cent of care homes reported more than 10 incidences during this period.

Thirty-five per cent reported that a member of staff had been injured as a result and 89 per cent reported staff being distressed by people with dementia's behaviour and many staff suggested that the recorded incidences were the tip of the iceberg.

When the Alzheimer’s Society published their study, it called for more training of care home staff on how to work with people with dementia and more access to anti-dementia drugs rather than antipsychotic drugs. Last year, the Health Foundation called for every prescription of antipsychotics to be backed up with a rigorous needs assessment.

Unfortunately there are still many who resort to sedating residents who display aggressive behaviour with antipsychotic drugs.

This is despite guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) which recommend antipsychotics should only be used as the last resort and a report from the Department of Health which found just one in five of the 180,000 dementia patients prescribed the drugs get any benefit from them.

Louise Lakey, policy manager of Alzheimer’s Society says: “Too often, dangerous antipsychotic drugs are prescribed to people with dementia who are agitated or distressed. Understanding the reasons why a person with dementia may be distressed is vital to ensuring that these drugs are only ever a last resort and that people with dementia are able to live their lives with dignity and respect.

“No one goes into the care profession to do a bad job. Nine out of 10 care home workers tell us they want more training on dementia. Staff should be both trained and empowered to make decisions that put the needs of people with dementia at the heart of their care.”

In a bid to address the lack of dementia training in care homes, the Alzheimer’s Society has just launched a new care home training programme.

It is hoped the training will lead to a drop in the amount of antipsychotic drugs used in care homes as, in an initial trial, the training reduced the use of antipsychotics in care homes by 50 per cent.

Antipsychotic drugs are inappropriately prescribed to 144,000 people with dementia and they can double the risk of death, treble the risk of stroke and can leave people unable to walk or talk.

The Focussed Intervention for Training of Staff (FITS) programme is being supported by £100,000 investment each from the Department of Health and HC-One.

This innovative new programme is set to benefit more than 5,000 people with dementia as it is rolled out to 150 care homes across the UK.

This includes a hundred homes from the HC-One care home group, which took over a third of the homes from Southern Cross when it went bankrupt.

Professor Clive Ballard, director of research at Alzheimer’s Society, believes FITS has the “potential to have a huge impact”.

He says: “By empowering staff with the knowledge they need to understand dementia and the person behind the condition it will help them to provide good quality, individually tailored care. Only then can we ensure that antipsychotics are a last resort and that people with dementia are supported to live their life with dignity and respect.” Staff in care homes across the country will receive training from the University of Worcester’s Association for Dementia Studies, which has been commissioned by Alzheimer’s Society to carry out the training of ‘dementia champions’.

The dementia champions will then be responsible for passing this training on to other staff working within the homes. It is expected that the first homes will start implementing the training in October.

Innovative dementia training is already an integral part of Care UK, which runs 80 care homes.

The company has found it has had a huge impact on residents’ behaviour.

Maizie Mears-Owen, head of dementia care at Care UK, puts on training programmes which enable staff to experience what it is like to have dementia.

During the training, care home staff wear goggles that blur their vision, put on gloves which reduce their sense of touch and listen to headphones emitting loud, white noise.

For the staff, it is a day when they are put in situations where they feel uncomfortable and confused and where nothing seems to make any sense.

‘I try and replicate what it is like to have dementia,’ says Ms Mears-Owen.

Staff find themselves being fed food that they cannot see, drinking tea from a plastic training cup and being asked several questions in quick succession without enough time to think of replies.

Staff are given gloves where some of the fingers are taped together replicating what it is like to have arthritis, making them realise how much we rely on sense of touch.

Sounds are muffled with cotton wool in their ears and Ms Mears-Owen will pull at the staff’s clothing.

“Most resist, some become anxious and some get angry. This is exactly how a person with dementia may react if something happens to them that they don’t understand or like. I want them to see that sometimes the behaviour of residents is a normal response, such as frustration, to an abnormal situation’.”

Sometimes it can be the simplest of things that makes all the difference.

“I was so pleased when a carer who had recently completed the course reported back that someone in their home had become agitated, asking for holes. This round green vegetable was on the white plate of the resident sitting next to her, but she saw green holes. The resident was given her peas and was happy and relaxed again and the member of staff could see a very real benefit of the experiential training – the ability to think differently," says Ms Mears-Owen.

Care UK carried out an evaluation of the dementia training and found incidents against members of staff had dropped by 40 per cent and incidents involving other residents had dropped by 21 per cent.

More information on training providers can be found at www.carehome.co.uk/suppliers_search_results.cfm/searchcategory/895

Latest Features News

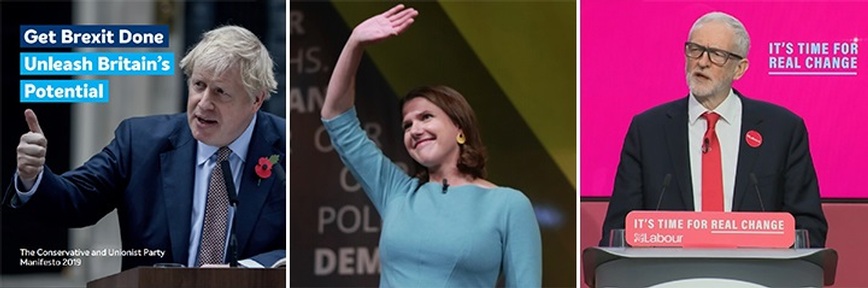

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig