Improving life for those with dementia starts with the person behind the disease

‘Developing excellent care for people living with dementia in care homes' by Caroline Baker documents the steps care homes can take to move towards providing truly person-centred care.

In her book, Ms Baker shows how care homes can give people a good quality of life by getting to know the personality of someone with dementia, as opposed to treating the symptoms and signs of the disease which now affects over 850,000 in the UK.

The guide embraces the challenges and concerns expressed by care homes and shows how person-centred care can be achieved without making huge changes to a care setting.

Ms Baker, director of Dementia Care at Four Seasons Health Care, carries out training and guidance. She and her team have created the specialist dementia care scheme PEARL, which aims to give staff all the tools they need to ensure they are ‘positively enriching and enhancing residents’ lives’ in all aspects of their job.

The scheme is built around the main principles of looking beyond a diagnosis and focusing on the person’s personality and passions.

Ms Baker said: “I started training as a student nurse in a psychiatric hospital and chose to specialise in dementia, which at the time was quite unusual as most opted to move into acute psychiatry. I found I had a passion for dementia as I realised at the time that we hadn’t got it right but I wasn’t sure how to make it right. I also worked on end-of-life care for people with dementia.

“The fundamental principles of the programme are to look beyond the condition of dementia to see the person as an individual and to understand their life history, their likes and dislikes. Through this we can deliver real person-centred care.”

Ms Baker encourages staff to move away from task-based activities and says providing food, personal care and accommodation should not be all that care workers are striving to do. Ms Baker tells staff that a quality of life should be achieved that can only be done by getting to know the person who they are offering care for.

Changing staff focus

Ms Baker explained: “When we first talk to care homes about person-centred care some think it is too complex working around the person and not being task focused, for example ensuring everyone has their cup of tea when they choose to have it.

“Staff initially think they cannot tailor care to every resident’s individual needs and that this is unachievable, however we help carers see that if they can reduce the distress of residents by providing person-centred care then it will stop distress happening in the first place.”

Ms Baker recounts the reluctance many experienced staff expressed about changing to a person-centred care approach but documents evidence of the improvements it has already made in care homes throughout the book.

During training, to help staff move towards the new style of caring, staff members are put in the same situations as some of their residents while task-focused care is carried out.

Real life experience

Showing rather than telling staff how to act, Ms Baker and her team often create real-life situations to put care assistants in the place of a resident to feel the difference person-centred care can make. More importantly, showing staff how non person-centred care make people feel highlights the importance of following the PEARL scheme.

Ms Baker said: “Things such as calling someone sweetheart or inadvertently ignoring them can isolate people, so we isolated staff on purpose and then carried out a reflective interview afterwards to reflect on how it felt to be treated in these ways.

“One man’s experience is memorable in PEARL training where staff empathise and experience how it might feel to be a resident in one of our homes. We used elements of malignant social psychology to show staff how they might make someone distressed or feel ignored even though they are acting without malice.

“One person became very upset after the task and explained that when they were being fed they kept turning their head away to indicate they wanted the trainer to slow down and they realised a woman they used to care for did the same. The member of staff had thought the woman meant she had had enough to eat and so in the past they had stopped feeding her, even though they now realised it was may be because they were feeding her too fast.

“One of my memories is at Granby Rose which was one of our pilot homes – it was very good already and the manager became very upset because although they had the highest regulator rating and Investors in People award, they realised there was so much more they could do to provide high quality specialist dementia care.”

Feeling like home

During the book, other contributors show readers how important person-centred care is to achieving a successful care home.

Techniques are described to allow care workers to meet residents’ safety, belongingness and love and esteem needs and reasons that, with these provided, a person can go on to meet their own self-fulfillment needs. This theory is based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs developed by American psychologist Abraham Maslow, which is used to indicate what motivates people in life.

Biggest hurdles ahead

A big hurdle facing Ms Baker and her team is changing the vocabulary used within care homes to respond to residents’ needs positively. She doesn't like the phrase ‘challenging behaviour’ because of its negative connotations.

While the NHS defines challenging behaviour as behaviour that puts person or those around them at risk, or leads to a poorer quality of life, Ms Baker wants more care workers to describe residents in this situation as having a ‘distressed reaction.’

She said: “‘Challenging’ can mean that the resident is seen to be at fault by challenging us but the main reason that people living with dementia may become distressed is because they may find it difficult to articulate their needs. We changed the language and stopped using challenging behaviour altogether.

“Most grabbing, shouting and ‘challenging’ behaviours occur when there is something the person needs, for example if the person is in pain.”

The term ‘distressing reaction’ was created after a member of staff at a training session highlighted that the word ‘behaviour’ places blame on the resident putting others at risk. Ms Baker believes that when people start changing the vocabulary the quality of care provided will improve across the sector.

Barriers keeping this from becoming a reality include the regulators who continue to grade peoples’ funding on how challenging they are.

She said: “Because many regulators still use the phrase ‘challenging behaviour’ and funding for people is reliant on proving a person is showing challenging behaviours, it is frustrating that these terms are still used in vocabulary.”

‘Developing excellent care for people living with dementia in care homes’ is available to buy here: http://www.jkp.com/uk/developing-excellent-care-for-people-living-with-dementia-in-care-homes.html

Latest Features News

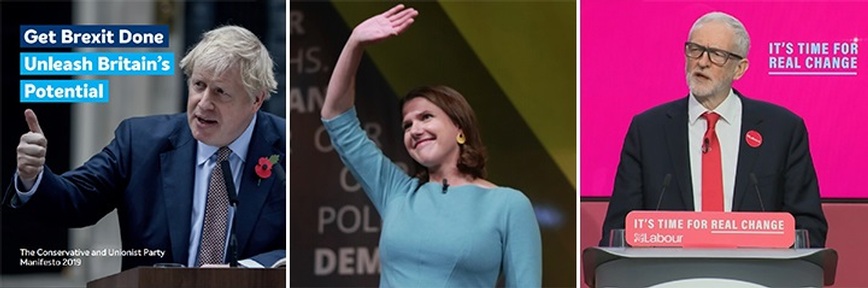

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig