Care homes urged to use cultural reminiscence in dementia care of ethnic minorities

A performer croons the words: “But I know we'll meet again, some sunny day…” and swiftly transports foot-tapping care home residents back to an era when war-time singer, Vera Lynn sang her song of solidarity to Britains in The Blitz.

But what if you are a dementia sufferer of a different culture, with no recollection of that era or have reverted back to your mother tongue and don’t understand what it all means?

African-Caribbean and South Asian UK communities are at greater risk of developing dementia than the English, white population but for those from a Black or Minority Ethnic (BME) background it can be more difficult to access the best care.

The Centre for Policy on Ageing estimated in 2011 that there are 25,000 people with dementia from BME communities in England and Wales. This figure is forecast to grow to more than 172,000 people by 2051- almost a seven-fold increase in 40 years.

'Society is not geared up to deal with this increase’ states the 2013 report ‘Dementia does not Discriminate’ produced for an all-party parliamentary group on dementia because of a ‘lack of access to culturally-sensitive services’.

Dementia is more prevalent among Asian and black Caribbean communities because high blood pressure, diabetes, stroke and heart disease, which are risk factors for dementia, are far more common among these communities than similarly-aged people of European origin.

Reliving a different past

Those with dementia may lose their most recent memories and relive times past. In their minds, they may act like the person they were 20 years ago.

This could be frightening for a black man who thinks he has just arrived in 1950s London where he experienced racism or an Asian woman who only remembers living in an Indian village.

Those with dementia may need ‘cultural clues’ to help them make sense of the world.

Research into older people from BME communities, reveals they want care to meet their cultural and religious needs. Specifically: • Sensitivity to religious beliefs and practices. • Interpreting services. • Halal, vegetarian and other culturally appropriate food. • Staff from similar backgrounds. • Same-sex workers for intimate personal care. • Opportunities to meet others from similar backgrounds.

Based on interviews with BME care home residents and staff, the Dementia Does Not Discriminate report found: ‘The most common type of abuse was lack of respect’. But over-emphasising the significance of a minority culture can also be problematic as life experiences are influenced by social class, gender and education.

Dr Karan Juttla, former senior lecturer at the association for Dementia Studies at the University of Worcester, believes a thorough understanding of an individual avoids stereotyping of needs according to presumed cultural characteristics.

So what should care homes do?

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) says person-centred care is the essence of good dementia care. This means valuing each individual and their unique personality, culture, life history and preferences.

Communication

As the symptoms of dementia develop and individuals begin to lose their short-term memories, longer-term memories may come to the fore. Many people migrated to UK when they were young men or women. If they were bilingual, they may lose the ability to speak their second language and speak only in their native tongue.

In the words of one Indian resident with memory loss: “I felt lonely. There was no one to talk to. They spoke a different language”.

Being able to use one’s own language is fundamental to identity and therefore dignity but practicalities in care homes may make this difficult. Research has found staff with linguistic and communication skills are a valued resource.

In the absence linguistically-skilled staff, other changes can help. Staff could, for example, learn a few words of a person’s language. Using pictures, the older person’s own vocabulary and interpreting non-verbal communication can be effective, although this requires effort by staff.

The chairwoman of the National Care Association (NCA), Nadra Ahmed says: “I’ve lived through this because my mother is Pakistani in origin and she had Lewy Body Dementia.”

This type of dementia, resulting from too much protein build up in the brain, leads to changes in concentration, language skills as well as memory problems.

Nadra Ahmed says: “The care home coped very well.

“There were some staff that understood the language she was speaking but we had keywords in her language written in the care plan such as ‘toilet’, ‘hungry’, ‘drink’, ‘sad’."

Keywords for objects were also stuck up around her room like ‘open’ next to her window.

“It was in the care plan that my mother liked her legs being covered in keeping with Islamic culture and staff knew that she covered her head when elder family members came to visit.

“A well-written care plan understood by all is vital.”

Meals

Someone with dementia might refuse meals or lose their appetite completely. One reason could be their food preferences have changed and they might have forgotten they like certain foods. A resident’s food tastes could link to the past age they’re reliving.

CQC inspectors look at people’s dietary needs and wishes, whether this is in their care plans and if staff had awareness of any needs for culturally appropriate food and drink.

The NCA chairwoman says: “Mum’s care home had a chef that prepared Asian food.

"The vast majority of providers are professional enough to cater to everyone’s needs.”

However, some may not agree with this latter statement.

The report ‘Dementia does not Discriminate’ reveals a lack of culturally-specific dementia services leads to some older people from BME communities preferring to use generic care services tailored to their culture.

The CQC regulates 17,000 care homes in England but the commission does not have figures on how many cater to a specific culture.

Aashna House, run by Sanctuary Care, describes itself as offering ‘culturally-appropriate services for residents with an Asian lifestyle. The care home’s CQC report states: 'The menu reflected the Asian heritage of the people who lived at the service. These meals were prepared in separate kitchens to adhere to cultural belief systems about food.'

On the subject of culturally-specific care homes, a CQC spokesman said: “It is of no more interest to us if a care home caters to a specific culture than whether they have extensive grounds.

“If they are not meeting the cultural needs of residents, then that is an issue.”

Entertainment

The NCA chairwoman says culturally-specific care homes have a place in the sector but warns against over-emphasising a particular culture to avoid stereotypes.

She argues: “Who says an Asian woman doesn't enjoy knitting with the best of them?”

Nadra Ahmed does however believe care homes can do more to celebrate a wide variety of different cultural and religious events and mark them in their social calendar along with Christmas.

As dementia develops, eventually the only memories the person can access are their childhood memories and the painful memories.

This may be distressing for people who migrated to the UK and experienced racism in their early life. It also makes reminiscence therapy designed to help those with dementia, tricky as it may stir up memories of a difficult period in people’s lives.

For a holocaust survivor, reliving the past can be particularly traumatic.

Care provider Jewish Care supports the Jewish community in the South East. It believes many care homes may struggle to help dementia sufferers from the Jewish community even if they aren't religious.

One man who struggled to care for his wife who had dementia contacted Jewish Care. He had no links with the UK Jewish community, had never been a synagogue member and had few Jewish friends.

The couple stepped away from their roots to rebuild their lives when they arrived in the UK as holocaust survivors. They didn’t want to talk about their horrific past.

But the past doesn’t stay in the past for those with dementia and so the Holocaust survivor asked the organisation to help his wife by tapping into positive cultural traditions.

A spokeswoman for Jewish Care said: “Where on average over 80 per cent of our residents are living with dementia, people, who may struggle to remember what they had for breakfast, are singing along to ‘ma nishtana’ with a smile on their face.”

Such traditions are often ‘hard wired’ so deep within someone that they last beyond other memories.

For residents not wishing to push buttons on the Sabbath, Jewish Care homes have lifts with no buttons that stop at every floor. And for care providers looking to support Jewish clients, Jewish Care runs a helpline.

But the spokeswoman warns: “If you really are going to meet someone’s cultural needs, it’s more than a tick box exercise."

Kosher meals can be ordered by any care home but the care provider believes making people feel ‘hamishe’ (Yiddish for cosy, at home) is only possible in an organisation where Jewish values are embedded like DNA.

Interacting with others

Making connections with others from the same culture can also help people with dementia reconnect with the world.

Surprisingly, 90 per cent of Jewish Care’s staff are not Jewish. It is volunteers from the Jewish community who regularly spend time with residents.

Delivering dementia care for minority groups is challenging but cultural connections can help. Prime Minister David Cameron’s drive for dementia care improvements by 2015 has been extended to 2020. But if Cameron’s army of ‘Dementia Friends’ hailed from many diverse cultures, their visits to minorities with dementia would be a therapeutic step in the right direction.

Latest Features News

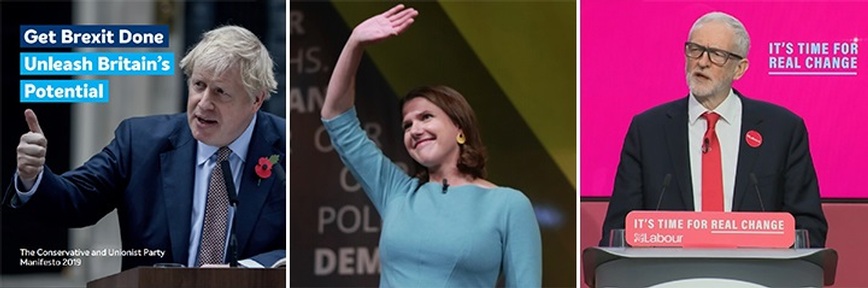

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig