'My wife found me in bed shaking and blamed my boss' but it was early onset dementia

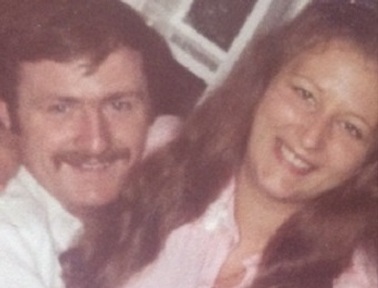

Ex-train driver Tommy Dunne worked his way up the corporate ladder to become a rail compliance manager of 19 people and still remembers the day his Alzheimer’s revealed itself.

He was at a business meeting with his company directors and says: “It was like a numbness coming over me.

“Like when a film comes off a reel…when it just runs out. I could hear a noise, it sounded like a compressor slowing down. That’s the last thing I remember. Everything was flickering and then it went blank.” The next thing Tommy remembers, he is in bed and his wife Joyce is standing over him. “I was sweating and shaking. My wife found me in bed shaking, so she asked my boss 'what have you done to Tommy?'"

Tommy’s doctor told Joyce “he’s had a complete shutdown”. The doctor’s misdiagnosis resulted in him being prescribed anti-depressants.

'Felt like a zombie'

Tommy retired early. One psychologist, one psychiatrist and four months later, a diagnosis of bipolar was given.

“I was on lithium and felt like a zombie. My wife kept fighting for us, saying ‘he hasn’t got bipolar, I know people with bipolar’.”

Fourteen months after Mr Dunne came home from work in the middle of the day, a brain scan led a psychiatrist to tell him he had early onset dementia.

Tommy was 58. It was 2012. He has not forgotten his response to the news.

“I felt a cold sweat running down my back. My life was over. I was going to be put in a home, in a chair. Left to watch other people.”

“My wife said it was a relief for her. My moods had changed, I was forgetful, and she realised why I had become so bad with money."

Retail therapy

And it wasn't just the unopened bills. Tommy had been unable to recognise coins for a while. After his diagnosis, he decided shopping could be made simpler. At the till, he opted to hold out his hand with coins and show the shop assistant a little card to say he had dementia.

The woman at the till took one look at the card and got on the microphone. ‘TRACEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEY! CAN YOU COME AND HELP THIS MAN? HE'S GOT DEMEEEENTIA!’

It was not just strangers who found his condition hard to deal with, his daughter, aged 28, and son at 41, did too.

When a newspaper wanted to photograph Tommy with his six-month-old granddaughter Freya at a dementia memory group session, his son intervened telling Joyce 'I’d rather she didn’t go in the paper because I don’t want her to be bullied when she goes to school'. Tommy is a warm, charismatic man but he becomes more pensive at the thought of his son's words. "I thought, I’ve got to change people’s attitudes.”

“My wife says for the first three years, it was like a grieving process.”

“She knows she’s lost someone. I may look like her husband, but she can’t get the same emotions back. “The hardest thing to deal with is losing the empathy. That connection with your wife. I know she’s my wife but I don’t have that empathy, the feelings a man has for his wife. I’m not the man she married.”

And he likens his behaviour with his wife to a Jekyll and Hyde change in mood. “If I’m watching a TV programme, it can be difficult to follow a plot, and she’ll talk to me and I won’t have heard it. I’ll say 'I didn’t bloody hear you speaking!'

"I go out of the room and come back nice as pie. I think why does she get upset? I may have forgotten what just happened but she hasn’t. She taped me once and I found it very hard to listen to and I thought, that’s not me.”

'Electric signals but plastic receptors'

He speaks of messages as electrical signals with some words missed because of what he describes as ‘plastic receptors’.

“A person with dementia uses twice the energy to have a conversation… it’s like we’re running a marathon. If I haven’t got the gist of what people said I will ask them again. People with dementia don’t want to appear stupid and won’t ask again. They lose confidence and go into silent mode."

Four months after being diagnosed, Tommy and his wife went back to the clubhouse where they play golf.

“The people came over to Joyce asking 'How’s it going? It must be awful for you'. I became invisible and the conversation continued as if I wasn’t there. I was talked about in the past tense”.

Five months after being diagnosed, Tommy was asked to join a group of 40 medical staff, psychologists, care workers and others to discuss dementia care. He saw himself as the ‘token service user' in the room.

“They started talking about what it’s like to have dementia. I said that’s not right”, not realising he’d spoken his private thoughts out loud.

Those words sparked a conversation that hasn’t stopped. He now has a working week telling people how they can improve the lot of those with dementia and has even had a hand in local authority policy changes.

Tommy and Joyce sold their house and moved into a bungalow after Tommy began missing steps and falling down the stairs.

Steps can look like a flat surface to someone with dementia. Tommy’s opinions in Liverpool Service Users Reference Forum (SURF) have seen local bus companies paint yellow lines on bus steps.

His thoughts have led him to give talks in care homes to advise them on how they can improve and his discussions with third year medical staff have been eye-opening.

“It surprises me that we are the first people that have been talking to medical students about dementia.”

He admits public awareness about dementia has grown since he was diagnosed but the struggle to be understood continues.

'Things get blurry like in Dr Who'

“The environment around you will change like an episode of Dr Who. Things get blurry and you’re somewhere else. Your brain forgets where you are and doesn’t recognise it.”

Tommy no longer drives. With no spatial awareness everything looks like it’s coming right at him. He gets the same feeling when strangers approach.

“I can get on a bus and have no concept of time. Everything will happen in a split second. A four mile journey…I blink and a mile is gone…I blink again another mile." It’s not unusual for Tommy to end up miles past his stop not being able to recognise where he is.

Tommy has helped the British Transport Police produce a staff training film on how staff should approach those with dementia. It's not rare for someone with dementia to be mistaken for being drunk or on drugs. They can end up in a cell when they cannot give rational answers and hit out when an officer touches them.

He also recently flew out to Budapest to speak at the 31st International Conference of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Life still goes on

Tommy also talks to those newly-diagnosed with early onset dementia to let them know life goes on and what to expect. He takes them to hear his speeches so that “when I can’t do it anymore, they can.”

He now leads a different kind of working week with his wife’s help.

After giving up work to look after him, Joyce, Tommy’s wife helps him put on his clothes to stop him wearing a jumper the wrong way round or walking around in two different types of shoes. She gets his bath ready and makes sure he gets in and out of it safely. She prepares meals and watches him take his medication, in case he drinks the glass of water but forgets to put the pills in his mouth.

Tommy says : “I really feel sorry for those people who live on their own. If Joyce didn’t tell me to take my medication I wouldn’t take it. I wouldn’t eat because I no longer feel hungry. I need to be reminded to drink. I usually take a sip to stop my tongue sticking to the top of my mouth. I wouldn’t go out. She tells me where I’m going and comes with me. She tells me 'You know, I’m bloody proud of you. But who’s there to tell her?'"

“I first met Joyce when we were 16 in an ice rink in Liverpool. She had long legs and a pretty face. She’s got the best personality I’ve ever seen in my life. The perfect woman. She’s never had a bad word to say about anyone. These are the things I should be telling her. It’s cruel that I’m not.”

Cure for the uninformed

“Sometimes I know what I want to say but it doesn’t come out. I can’t remember what the word is or something else comes out."

While there is no cure for Alzheimer’s, there is a cure for people’s uninformed, if well-meaning, responses to Alzheimer’s.

Tommy says: “The reason I don’t get frightened in a situation like a conference is that I’m in a room full of people that would understand that could happen. It’s when you tell someone new you’ve got dementia, that’s when you feel it.”

Latest Features News

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig