People with 'complex' and 'social jobs' could have reduced risk of dementia

Certain genes and lifestyle factors such as the type of job someone has could help to increase reliance against a person’s chance of developing Alzheimer’s disease, according to the latest research.

Speaking at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2016 in Toronto, researchers revealed that certain resilience factors may differ between men and woman and could counteract the negative effects of poor diet on cognition.

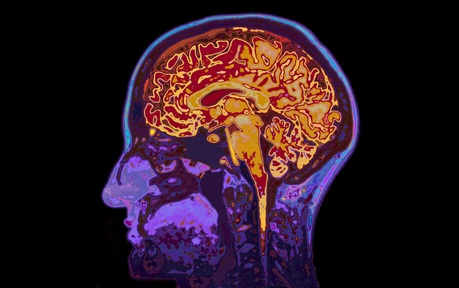

Studying factors such as the number of years spent in education, having a complex job and participating in regular activities that challenge the brain, can help to build resilience and build up a ‘cognitive reserve’. Cognitive reserve is the ability of the brain to withstand some level of damage without any loss of function.

Director of research and development at Alzheimer’s Society, Dr Doug Brown said: “Dementia is not an inevitable part of getting old. Increasingly, research is showing us that there are things we can do throughout our lives to reduce the likelihood of developing dementia.

“This research builds on what we already know about the importance of keeping our brains active to improve memory and thinking as we age, whether this is through having a complex job or hobbies and pastimes that challenge the brain and keep you connected to friends and family.

“These findings reinforce the powerful message that we should be taking a lifelong approach to maintaining good brain health. Over the next 10-years, Alzheimer’s Society is committing more than £150m to research to not only find a cure for dementia, but ways to prevent it developing in the first place.”

Stimulating lifestyles and poor diet

Maintaining a mentally active lifestyle through regular exercise, education and having a complex job and socialising can help to protect against the effects of a poor diet on a person’s risk of dementia, according to researchers at Baycrest Health Sciences in Toronto.

Scientists studied 351 adults who were living alone in Canada and consuming a 'western' diet and gave them a score of ‘cognitive reserve’ based on their academic achievements in the past, job complexity and social habits.

Study participants were consuming a ‘western’ diet consisting of red meat, processed sugary foods and white bread and potatoes, and after three years showed accelerated rates of cognitive decline. Furthermore, accelerated rates of cognitive decline were also true among those with a low cognitive reserve score (182 people). Researchers revealed that a ‘western’ diet did not have a negative effect on cognitive performance in those who led stimulating lifestyles (169 people).

Dr Brown continued: “People who regularly challenge their brains through education, work and leisure activities tend to have lower rates of dementia in later life. This study broadens out our understanding to suggest these activities could help to protect the brain by compensating against the negative impact of an unhealthy diet.

“This shouldn’t become an excuse to continue eating stodgy and sugary foods, though. Getting a healthy balanced diet that’s low in red meat and high in fruit and veg is still one of the best ways to reduce your risk of dementia throughout life.”

Social jobs offer greater protection

Researchers at the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Centre and Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute further revealed that people who have more complicated or mentally challenging jobs were able to better withstand damage to the brain, commonly associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

People with jobs such as: social workers, teachers, lawyers and doctors were considered to be best protected, compared to those with more physical jobs such as shelf-stackers, machine operators and labourers.

Researchers scanned the brains of 284 healthy people who were thought to be at risk of dementia, assessing the scans for white matter hyperintensities (WMH) which indicate damage to the brain - commonly found in those with Alzheimer’s disease. The results were compared with the participants’ cognitive function and the type of work they have done in the past or were doing at the time of the study. The study indicated that people who worked with other people, rather than data or physical things saw the most protective benefit and were less likely to affected by brain damage or WMH.

Those who had more complex jobs throughout their lives were often found to have more WMH but still performed as well as their fellow participants in cognitive tests. The results indicate that those with more complex occupations may have brains that can tolerate more damage without experiencing any deterioration in cognitive ability.

Dr Brown, continued: “Everyone’s brains experience some wear and tear as they get older – in some people this will go unnoticed but for others it can contribute to the development of cognitive decline and dementia. This study suggests that complex jobs involving working with others might help to make people more resilient to the damage so that they are less likely to develop problems with memory and thinking.

“It’s incredibly positive to see that there are things we can do in life that could help our brains as they age. For many of us, the complexity of our job is not something we can easily change, so we need to see more research into other ways for people to build up their resilience to dementia.”

Lifestyle changes

Researchers from the Victoria Longitudinal Study in Western Canada found that lifestyle changes coupled with environmental factors could help to protect against the Alzheimer’s disease risk genes: Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ?4 and Clusterin (CLU) C.

Scientists studied 642 people aged 53-95 without dementia over a nine-year period. Participants were tested for the risk genes: APOE?4 or CLU-C and had regular memory tests to determine if their memory had declined or stayed the same over the nine-years.

The study revealed that women with one of the risk genes demonstrated better lung function, walking speed and social skills which were all linked to stable memory performance in tests. While men and women who showed stable memory performance were found to have spent longer in education, have better muscle tone and participate in regularly mentally challenging activities such as doing taxes or playing bridge, than those who experienced memory decline.

Dr Brown concluded: “One of the most common questions people ask is whether dementia is inherited. Unfortunately, there isn’t a simple answer to this - because a family member has dementia doesn’t always mean you will develop it too. This study shows that genetics can only give us part of the picture when it comes to the causes of memory loss.

“Over two-thirds of people with dementia are women, and we don’t yet fully understand why men and women develop dementia at different rates. This study provides important insights into how lifestyle factors can interact with genetics to affect men and women’s memory differently. Advances like this may ultimately help us to develop gender-specific advice for those at risk of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Latest News Analysis

04-Sep-19

Extra £1.5 billion announced for social care in Chancellor's Spending Review

04-Sep-19

Extra £1.5 billion announced for social care in Chancellor's Spending Review

02-Jul-19

Department of Health forced to rethink care homes' nursing rates after legal challenge

02-Jul-19

Department of Health forced to rethink care homes' nursing rates after legal challenge

18-Jun-19

Overnight care workers forced to sleep in offices and told 'bring your own bedding'

18-Jun-19

Overnight care workers forced to sleep in offices and told 'bring your own bedding'

14-Jun-19

Back in the closet: Third of care home staff have had no LGBT+ awareness training

14-Jun-19

Back in the closet: Third of care home staff have had no LGBT+ awareness training

11-Jun-19

PM candidates on social care: Rory Stewart calls fixing care an 'unfinished revolution'

11-Jun-19

PM candidates on social care: Rory Stewart calls fixing care an 'unfinished revolution'