'Senile', 'suffering' and 'past it': Challenging negative dementia stereotypes and ageism in the care sector

‘Demented’, ‘senile’, ‘suffering’ and ‘past it’ are words often used to describe older people and those with dementia. Yet language that is negative and unappealing perpetuates ageism and negative stereotypes about older people and those living with dementia.

It is often thought that positive reinforcement can be used to encourage good behaviour and a positive outlook. This is something that is equally true when using negative language to describe someone and is crucially important in the social care sector to ensure that care is personalised and appropriate to someone’s needs.

Writing in a recent blogpost about the impact of negative language and ageism, Phil Richards communications assistant at the Centre for Ageing Better said: “If you tell someone something often enough, they eventually start to believe it. This can be a wonderful thing, used to reinforce positivity. But it can also be extremely damaging when you’re repeating words that constantly undermine.

“Using negative language about older people is simply ageism – and this unappealing habit has become so mainstream we hardly recognise we’re doing it. But the effects and consequences of our choice of vocabulary run deep.

“Not only is our use of language having negative impacts on older individuals, but it also affects the way society views and treats them. Research from the Equality and Human Rights Commission on the Processes of prejudice shows that subtle, implicit, forms of prejudice can be manifested through language; and that stereotypes can influence our judgements and behaviour even if we don’t agree with them.”

The internet and the media are full of negative language about older people and people living with various health conditions and disabilities, encouraging the mindset among members of the public that it is acceptable to refer to people in this way, especially people living with dementia.

In June 2012, The Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) launched the Dementia without Walls programme. The programme ran until the end of 2015 to help people with dementia to be better understood, more included, more connected and better supported by their local communities and wider society.

The programme saw JRF develop a range of partnerships, commission projects and publish reports, papers and films to help people to engage meaningfully with those living with dementia.

In late 2014, the Dementia Action Alliance (DAA) held a conference for people living with dementia about how they wanted to be reflected in the media which saw the launch of the Dementia Words Matter campaign.

The campaign was led and promoted with the Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (DEEP), which also worked with people with dementia to produce a language guide containing words and description of dementia that they would prefer were avoided.

Chief executive of Care England, Martin Green advocates the use of sensitive language when talking about both older people and people living with dementia. He said: “One of the challenges we face, is that we live in an ageist society, and despite the equality and human rights act having age as a protected characteristic, there is little or no challenge from the equality and human rights commission to the way in which age is portrayed.

“Ageism is one of the areas which goes completely unchallenged in most of society, and the casual negative attitudes to age, would not be tolerated if they were about race, sexuality, gender or disability.”

The effects of negative vocabulary are far-reaching, not limited to affecting the way older people and those living with dementia are perceived and how they are treated or referred to, but the way they feel about themselves.

Tommy Dunne was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at the age of 58 and worked with DEEP during the creation of the language guide. Recalling his experiences after his initial diagnosis, he said: “When you get dementia you gain a super power; you have the ability to become invisible.

“When I'm in a room full of people I know, I feel the loneliest person in the world, because people will talk over me, around me, about me, but never to me. Yet when I'm in a room with strangers, they talk to me, until I say the magic words, 'I've got dementia' and hey presto, I turn invisible.

“Just because a person with dementia does not speak does not mean they don't understand or that they don't want to communicate. I want to take the fear of a diagnosis of dementia away and the best way to do this is through educating people.”

Wendy Mitchell was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s in 2014 and writes a blog to raise awareness of the lack of research into Alzheimer’s. Writing about how people with dementia are portrayed she said: “I so often get upset, annoyed, frustrated, when the media refer to those of us living with dementia as ‘sufferers’ and speak of the ‘epidemic’.

“A diagnosis of dementia is bad enough – that’s the devastating news. But that’s where negative language can stop and positive language begin. If someone tells you day after day that you’re a ‘sufferer’, you end up believing it. It has a negative impact on your wellbeing. We ‘struggle’ daily to out manoeuvre the challenges we face but, often with help, we can find ways of overcoming those struggles.

“In nearly every case where the word ‘sufferer’ has been used, it could be replaced simply by ‘living with’."

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) is one of more than 400 signatories committed to encouraging appropriate language through the Dementia Words Matter campaign, with its chief executive, David Behan, saying: “Using language like 'a person suffers from dementia' perpetuates fear and stigma and is completely at odds with the aspirations of people living with dementia. They tell our inspectors that they want to live well and be supported to do so.

“CQC has a vital role in making sure that people receive care that is safe, effective, compassionate and high-quality. We know how important language is in ensuring that care is respectful and person-centred."

Alzheimer’s Research UK is also on the list of signatories. Laura Phipps, head of communications at the charity, said: “A diagnosis of dementia can be life-changing, but it doesn’t mean that a person should be defined by their medical condition. .

“Dementia now has more public attention than ever before, but sadly misunderstanding about the condition still persists today. The language we use about dementia has a real impact on the way the condition is viewed and understood across society, and it’s vital that the words we choose when talking about the condition are accurate, balanced and sensitive.”

Now the Dementia Words Matter campaign is used as an educational resource, helping both health and social care practitioners, the wider public and the media to provide sensitive and appropriate support and coverage for people with dementia.

Communications officer at the DAA, Louise Thomas said: “We know from ‘Dementia Words Matters’ that the appetite to treat people with dignity and respect is strong amongst the care sector, and there is a recognition that individuals face social isolation through negative perceptions.

“The Dementia Words Matter campaign is the flagship campaign tackling inappropriate language in dementia care and support and encourages people to see past the fear and stigma traditionally associated with dementia, and see the person and their whole lives. That way people are less likely to be victimised and more likely to be active participants in society.”

For more information and to read the DEEP Dementia Words Matter guide to language, visit: http://dementiavoices.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/DEEP-Guide-Language.pdf

Latest Features News

25-Nov-19

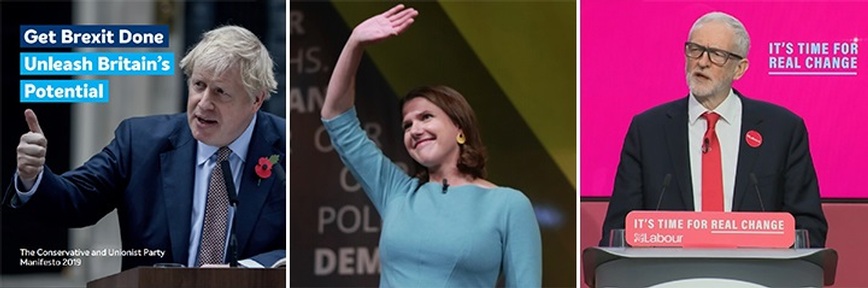

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig