What's it like to have autism? 'My senses were under attack'

As an autism tourist, I was about to take a trip and enter a new world. This new place, courtesy of a blacked-out van, was immediately unnerving. Visually it felt like the floor was escaping from me. Suddenly vulnerable. Unsteady on my feet...as if the ground was uneven and I would fall...it was my vision showing me a blurry, off-kilter world...so I held onto a door handle.

I was taken by the hands and led into a dark room, where green, red and blue dots of light raced around the place. A screen showed a clock loudly tick-tocking, a tap slowly drip dropping, a vacuum cleaner sucking out the quiet from the room.

I had been told to sit down and watch a screen in this darkened space but even the chair was hard and unwelcoming, with its strange ridges. The woman in the corner watched as I scrutinised the images being shown. I had been told to wait for instructions.

'Baby powder and fresh bread'- a strange perfume

A few instructions came occasionally spliced inbetween much banging, splashing and tick-tocking. Most of the time, my senses were under attack. An onslaught of sounds, sights, textures and smells closed in. Baby powder, coffee and fresh bread wafted in the air making a strange perfume. I felt overwhelmed. A little anxious. I wanted to get up but the woman told me to sit down again, and again, to listen to what seemed like an army of unwanted guests.

Sporadically came five or six basic instructions. I could recall: ‘Write your mother's maiden name on the blue post-it note’; ‘spell out the word autism on the wooden blocks’; ‘find seven green tiddlywinks’; ‘find the five of spades’.

Small victories felt huge

Trying to act on the information and get started, I was restless. Distracted. Frustrated by this new normal, the desire to get up and do something was great. Eventually, I broke free from my…carer?... and rushed to the boxes at the opposite end of the room. Lifting the lid, I found it was a perplexing task to pick out green tiddlywinks amongst a multi-coloured box of them. I brought them close to my face. The dark, the flashing lights and blurry vision had distorted the colours. Like someone had washed and laundered my senses and given me two odd socks that didn’t fit.

Colours I realized were not my only problem. My hands wrapped in disposable gloves and what seemed like bumpy, gardening gloves with a bit of reinforced plastic in the odd finger, messed about with my gripping skills.

Reaching another box, I wondered...how many 2ps had to be counted out? Twenty pence worth, I guessed, and put it where?… in the blue piggy bank? Box number three had me diving into a scattered pack of playing cards and cack-handedly managing to direct my digits to pluck out a five of spades! This small victory felt huge.

All the while everyday household sounds were played at full whack in my ears. As I wrestled with basic tasks, the clock wound down and time was up. I left weary but relieved to be free of this room.

'Seams distress him'

Was this autism? The woman present in my Autism Reality Experience, Chelsey Cookson should have some idea. Her son Lewis was diagnosed with autism when he was four-years-old. He is now nine and she is keen for people to know about the sensory struggles he has battled with.

She says of the tour: “It’s specifically designed and geared up to give somebody an idea of what it’s like when somebody has too much sensory stimuli.” Describing Lewis’ autism, she says sensory overload can make a person over-sensitive to tactile information.

“It can make it quite difficult for him to manage day-to-day things. He turns the socks inside out because the seams are distressing him.

“I’m much more patient and much better at preparing him for environments where I think there could be some triggers for him feeling quite anxious and distressed.”

A quest for empathy

Around 700,000 people in the UK are on the autism spectrum. Autism is a lifelong disability that affects how a person communicates with and relates to other people, and while everyone's experience is unique, some 96 per cent of people with autism have a sensory processing disorder. They see, hear and feel things differently. The tour forces a person’s sensory processing system to work hard.

Anyone can have an over or under-responsiveness to one of the senses. Ms Cookson talks of 22 senses gifted to the human body. The Autism Reality Experience plays around with the senses of sight, hearing, smell, touch, proprioception (the ability to tell where body parts such as muscles and joints are, relative to other body parts) and the vestibular system which equals the sense of balance and movement and is closely linked to gravity and attention.

People with autism also struggle with social communication, social interaction and anxiety issues.

Occupational therapists, autism specialists, parents, as well as trainers from the National Autism Society who have autism, road-tested the tour and their feedback has honed the final experience.

She says: “It was important to involve people with autism because they can tell you how realistic it is.”

The Autism Reality Experience, showcased at October's Care Show 2017, is run by Training 2 Care UK, the same Essex company that created the Virtual Dementia Tour.

Staff from care homes, hospitals, police forces and prisons have been through the Autism Reality Experience, which can be tried across the UK because this autism world is conjured up in a van.

Ms Cookson, who works for Training 2 Care UK, is hopeful greater understanding of autism gained from the tour will breed greater empathy to help educators and care workers support others. She adds: “Autistic people may need lots of vestibular input. At school, an autistic person may be moving in order to regulate themselves to listen. To concentrate they need to move.”

When asked how her son is, she says: “He is doing well. He had been struggling to sleep. When we created this reality experience, I had gaps in my knowledge. I've learned more." Having learned a bedsock could help her son, she got him what looks like a bedsheet to use at home and at friends' sleepovers. It replicates weighted therapy by providing compression on the body.

She adds: "It has stopped him being up all night.”

Latest Features News

25-Nov-19

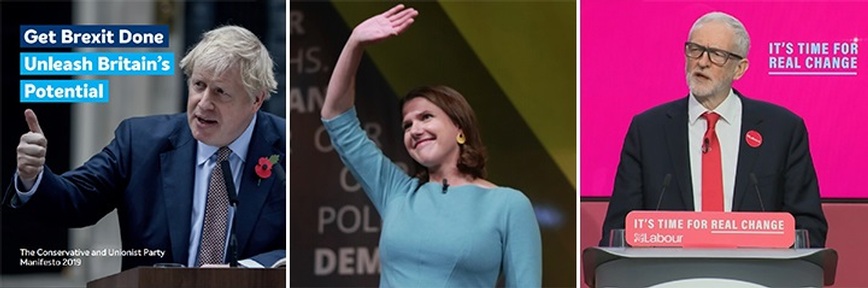

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig