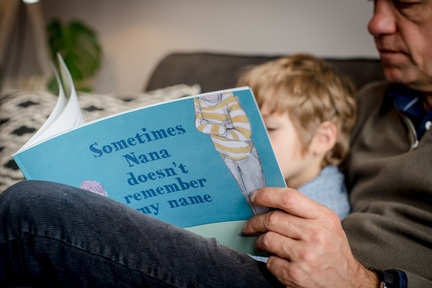

Picture book on dementia helps children understand Granny's behaviour

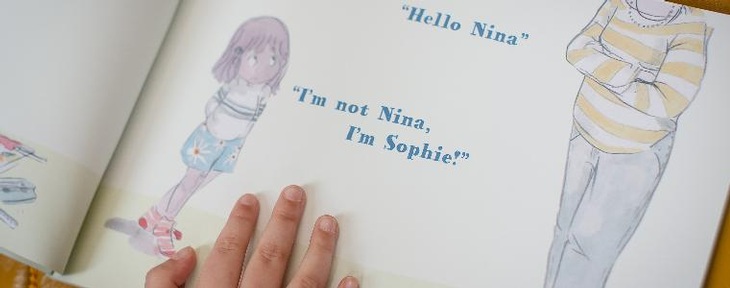

Sometimes Granny doesn't remember my name. It’s like hundreds of names are spinning around in her head and she just picks one. She does unusual things too. She gets lost in her own house and puts orange juice on her cereal. What's wrong with Granny?

These are some of the questions a child may struggle with when a loved one is living with dementia. So how do you explain the condition to a five-year-old?

“Whilst it’s natural to want to protect children, it’s important to be honest and explain things calmly,” says Matthew Adams, founder of the Ally Bally Bee project. “Dementia affects every family differently, which is why we have created a personalised children’s book that is relevant to every family’s situation and is designed to make these conversations a little bit easier.”

The Ally Bally Bee Project was set up three years ago and creates personalised books for young children, using names of their family members living with dementia and examples of their specific behaviours, all with the aim of explaining why they have changed.

Mr Adams explains: “My wife’s grandmother had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in her 90s and I recall one evening, sitting around the table with the family, discussing the way her gran had been acting and the things she had been saying. It was tricky enough for us adults to make sense of – so how would a child make sense of it? It got me thinking: how would I explain granny’s dementia to my daughter?”

The personalised picture book, thought to be the world’s first, was illustrated by university student Daisy Wilson and written by Elvira Ashby – a children’s author, a Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) and a mother of two young children. The story took 12 months to develop and involved people living with dementia and medical professionals along the way.

A journey through a loved one’s brain

Throughout the story, the child journeys through their loved one’s brain. Accompanied by ‘Super Doc’, children learn about the different lobes of the brain, how the dementia affects that area and how it affects the person’s behaviour.

For example, the hippocampus is depicted as a room full of memory jars of all shapes and sizes, but the dementia has knocked some of the jars over making it tricky for Granny or Grandpa to find the right memory.

Mr Adams said: “Despite the tragic nature of the illness, the relationship between grandparent and grandchild can still be tender, so we wanted to explain dementia in a way that’s relevant, whether Granny’s pouring orange juice on her cereal or Uncle John’s getting lost in the supermarket, because everyone’s got a different story to tell.”

'Dementia and its associated behaviour is nobody’s fault, least of all theirs’

There are currently 850,000 people living with dementia in the UK, with numbers set to rise to over one million by 2025.

The condition can create challenging situations for families and social groups, and it can be hard to know how much to explain to children and young people. Whilst it is natural to want to protect children from difficult or confusing situations, Alzheimer’s Society says it is important to explain what is going on. There are a number of reasons for this, including:

• Children and young people are often aware of underlying atmospheres and tensions, so it can be reassuring for them to understand what the problem is

• Although the news may be distressing, children and young people may find it a relief to know that the person’s behaviour is part of their dementia and is not directed at them

• It can be more upsetting for the child or young person to find out later than to cope with the reality of what is happening. If a child is not told, they may find it difficult later to trust what someone close to them says

• Seeing how people around them cope with difficult situations helps young people learn valuable skills about dealing with tough and distressing situations, and being able to manage painful emotions.

Chief executive of Alzheimer’s Research UK, Hilary Evans, said: “Dementia doesn’t just affect individuals, it impacts whole families and communities. Despite how common it is, there are still a lot of myths and misconceptions surrounding dementia. For children, especially those with a close relative like a grandparent or parent with the condition, it can be a particularly difficult experience.

“It’s important for young people to appreciate that changes in the way a family member may be behaving are nobody’s fault, least of all theirs, but the result of changes affecting how the brain works. Educating the next generation about dementia is critical if we are to overcome the stigma that still surrounds the condition today.”

The next step for The Ally Bally Bee Project is to translate the book into other languages, starting with Finnish and Swedish, to reach more families affected by the difficulties of dementia.

An illustrated story costs £20, with some of the profits going to appropriate charities. For more information go to: www.allyballybee.org

Latest Features News

25-Nov-19

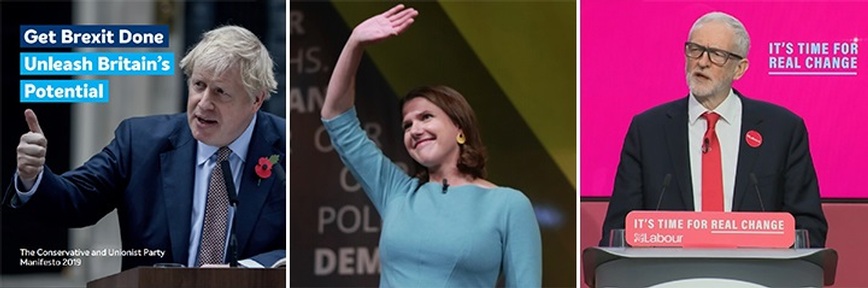

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

19-Sep-19

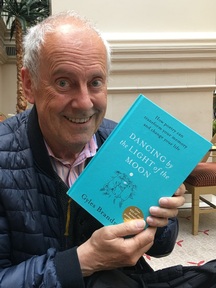

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig