Violence and aggression in care homes: Care workers getting punched isn't 'part of the job'

“He had her against the wall with a knife to her throat” says a relative describing how vascular dementia dramatically changed his uncle’s behaviour. However violence “always has a trigger” says an Alzheimer’s Society trainer who urges care workers to find it.

’Some care staff say getting punched is just part of the job’

Kicking, hair pulling, biting, swearing, hitting and spitting are not uncommon occurrences in care homes and care workers are at the receiving end.

Some 71 per cent of care workers claim to have faced both verbal and physical aggression in their jobs, according to a survey by Able Training Support.

The anger, confusion and fear that people with dementia experience can result in aggressive and sometimes violent behaviour, which can put care workers lives at risk.

Last week, a 95-year-old man believed to have dementia was arrested by police after a care worker was found dead at her client’s north London home. A neighbour heard a scream and paramedics found the 61-year-old woman with head injuries. She was rushed to hospital but died the next day.

It is no wonder staff feel scared, intimidated, stressed out, demoralised and depressed and that the sector is facing a high staff turnover, with Andy Baker, head trainer at Able Training Support saying: “Some care staff say getting punched is just part of the job”.

When asked how care home staff can care for others with confidence, Sue Brewin, associate trainer at Alzheimer’s Society says finding the trigger for violence is vital. While it might take a while to find the cause, she makes it part of her business.

’I kicked him hard’

As part of her job, every week, Ms Brewin is invited by care providers to go into care homes to observe staff, residents and interactions between the two. Delving into the semantics of her job, she prefers the term “distressed behaviour” rather than the word ‘violence’, when talking about the negative physical reactions of those with dementia.

Ms Brewin, whose 75-year-old grandmother died of dementia, reveals how over 20 years ago her own trainer blocked her path to the door at the end of a long training session on violence. He repeatedly refused to let her leave to get home to her four young children and unaware she was being used as a guinea pig, she admits: “I kicked him hard”.

“I don’t have dementia”, she says but is now keenly aware “it was done to make me understand how someone else would feel. I still remember those feelings 22 years later”.

“Swearing, hitting, kicking, shouting, withdrawing is all distressed behaviour. We can communicate how we feel” but she notes in someone with dementia, “the ability to communicate verbally deteriorates.” Impaired logic and hearing also take away the person’s ability to connect as we’d expect.

Staff can visibly recoil when a resident swears at them. “Don’t take it personally” she says. Staff may instinctively react and withdraw but it’s important not to.

Dementia can damage a person’s left temporal lobe in the brain, where everyday formal words are stored. Because they can no longer access it, they access instead the undamaged right lobe - a source of rhythm, jokes … and every slur and swear word the person has ever heard. So swear words becomes a person’s way of reaching out to express something.

Imagine an elderly woman smiling at you, calling you over and sweetly stroking your hair, cradling your upturned face as if you were a baby, before leaning in to call you a “b**tard”. Ms Brewin has been there.

“We need to communicate in a way that does not challenge” she says. “Our approach can make a difference. How do we feel when somebody tells us to calm down?"

Getting to know someone’s background is advised, but if someone wants their mother, telling them their mum is no longer alive will only increase their stress. She advises simply telling the resident: “I see you are really upset, but it’s okay, I’m here now, we’ll sort it.”

She says it’s not necessarily the words but the meaning of their words that matter. “I’d be looking into the emotion of what does ‘Mum’ mean? Do you want your mum because you want a hug, have something to confide or feel pain?”

The International Association On The Study Of Pain has reported 80 per cent of older people living in care settings experience chronic pain.

“Has anybody ever told you’ve got beautiful blue eyes?”

Staff can fear distressed behaviour and Ms Brewin urges care worker to “avoid avoidance”. “We often see care staff avoiding things.”

She explains how during a visit to a care home, she saw a man with his fists up screaming “Get out! Everybody get out!” and was told by a care worker “Oh it’s Joe! He always does that”. But with no prior knowledge of the resident, Ms Brewin still didn’t leave him to scream.

“I stood in front of him, held his fists and made eye contact. “I said ‘Has anybody ever told you you’ve got beautiful blue eyes?’ ‘Yes’, he said ‘lasses, when I was ballroom dancing’”. She told him: “I can’t dance.” So he replied: “I’ll show you”. And so, the two ended up dancing in the corridor.

But what was the trigger? The resident began shouting at breakfast time because he believed everyone was in his house eating his food. Since then, staff have arranged for him to dance to music with female residents in a separate room each breakfast time.

She advises: “Don’t label a person because that label can stick. Always leave the person with a good emotion”.

Brutal truth: ‘Some people are not nice people’

Of her care home visits she says: “90 per cent of the time I’m doing observations, I can see the trigger”. For example, staff approaching someone with dementia from their left or right side “can make them jump”. They may have soiled themselves and can’t express it.

But finding a trigger for violence can unearth a brutal truth. “We have to understand that some people are not nice people. Because they have never been nice people.”

Referring to a man who moved into a care home she says: “On the first day he’d hit three women.” His daughter explained it was her dad’s usual behaviour with the words: “He’s hit my mum all my life”.

With severe dementia, a person may not be able to identify whether the person in front of them is a man or a woman and may not understand what they say. For the non-verbal, she says, staff can use non-verbal cues to, for instance, get a resident dressed.

She advises a care worker approach the person from the front, get to their eye level, make eye contact, smile and use short sentences. “Stay at arm’s length with your hand out - like a handshake - to see if they want to connect with you first.”

If they do touch your hand, she suggests using palm to palm contact. “Hold their clothes up so they can see them”. She says try putting a warm towel round their shoulders to preserve their dignity (rather than have them sitting naked) and demonstrate putting the clothes on yourself.

She recommends workers get the right training and care homes get enough staff. This, she believes, could reduce high staff turnover and workers can feel confident about their skills. “It takes time”, she admits but believes spending that time to, for instance, comfort a crying woman can “save hours of distress throughout the day”.

Latest Features News

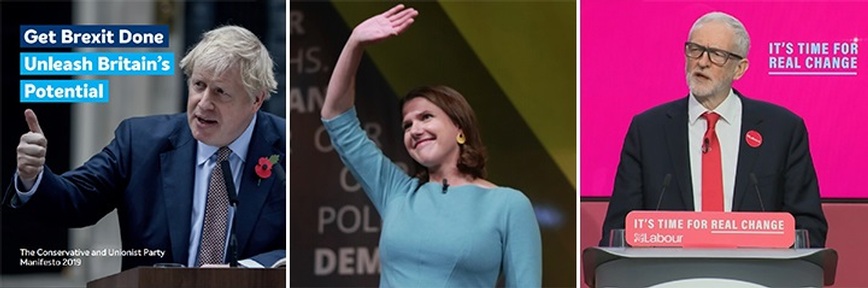

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

25-Nov-19

2019 Election: Boris Johnson leaves social care in 'too difficult box' but Labour vows to end 'crisis'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

18-Oct-19

Podcast: Wendy Mitchell and dementia: 'My biggest fear is not knowing who my daughters are'

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

27-Sep-19

Exclusive: Care minister backs care workers' call for time off to grieve and attend funerals

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

19-Sep-19

Podcast: Gyles Brandreth says poetry helps ward off dementia

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig

30-Aug-19

Edinburgh Fringe funnyman joins comics facing toughest audience at care home gig